What kitchen tool used to "cut-in" when baking?

A kitchen utensil is a modest hand held tool used for food preparation. Common kitchen tasks include cut food items to size, heating nutrient on an open up fire or on a stove, baking, grinding, mixing, blending, and measuring; different utensils are made for each task. A general purpose utensil such equally a chef'due south pocketknife may be used for a multifariousness of foods; other kitchen utensils are highly specialized and may exist used simply in connection with grooming of a particular type of nutrient, such equally an egg separator or an apple corer. Some specialized utensils are used when an operation is to be repeated many times, or when the cook has limited dexterity or mobility. The number of utensils in a household kitchen varies with time and the fashion of cooking.

A cooking utensil is a utensil for cooking. Utensils may be categorized by employ with terms derived from the word "ware": kitchenware, wares for the kitchen; ovenware and bakeware, kitchen utensils that are for use inside ovens and for baking; cookware, merchandise used for cooking; so forth.

A partially overlapping category of tools is that of eating utensils, which are tools used for eating (c.f. the more than general category of tableware). Some utensils are both kitchen utensils and eating utensils. Cutlery (i.east. knives[1] and other cutting implements) tin can be used for both food preparation in a kitchen and as eating utensils when dining. Other cutlery such every bit forks and spoons are both kitchen and eating utensils.

Other names used for various types of kitchen utensils, although not strictly denoting a utensil that is specific to the kitchen, are according to the materials they are made of, again using the "-ware" suffix, rather than their functions: earthenware, utensils made of clay; silverware, utensils (both kitchen and dining) made of silver; glassware, utensils (both kitchen and dining) made of drinking glass; and so along. These latter categorizations include utensils — made of glass, argent, dirt, so forth — that are non necessarily kitchen utensils.

Materials [edit]

Kitchen utensils in bronze discovered in Pompeii. Illustration past Hercule Catenacci in 1864

Benjamin Thompson noted at the start of the 19th century that kitchen utensils were commonly fabricated of copper, with diverse efforts fabricated to forbid the copper from reacting with nutrient (particularly its acidic contents) at the temperatures used for cooking, including tinning, enamelling, and varnishing. He observed that iron had been used as a substitute, and that some utensils were made of earthenware.[2] By the plow of the 20th century, Maria Parloa noted that kitchen utensils were made of (tinned or enamelled) atomic number 26 and steel, copper, nickel, silver, tin, dirt, earthenware, and aluminium.[3] The latter, aluminium, became a popular material for kitchen utensils in the 20th century.[4]

Copper [edit]

Copper has good thermal electrical conductivity and copper utensils are both durable and attractive in advent. Yet, they are too comparatively heavier than utensils fabricated of other materials, require scrupulous cleaning to remove poisonous tarnish compounds, and are not suitable for acidic foods.[v] Copper pots are lined with tin to prevent discoloration or altering the taste of food. The can lining must be periodically restored, and protected from overheating.

Iron [edit]

Iron is more decumbent to rusting than (tinned) copper. Bandage iron kitchen utensils are less prone to rust by fugitive annoying scouring and extended soaking in h2o in order to build upwards its layer of seasoning.[6] For some iron kitchen utensils, water is a particular problem, since it is very difficult to dry them fully. In particular, iron egg-beaters or ice cream freezers are tricky to dry, and the consistent rust if left moisture will roughen them and possibly clog them completely. When storing atomic number 26 utensils for long periods, van Rensselaer recommended coating them in not-salted (since common salt is also an ionic compound) fatty or alkane.[vii]

Iron utensils have lilliputian problem with loftier cooking temperatures, are elementary to clean equally they become smoothen with long apply, are durable and comparatively strong (i.e. not as prone to breaking as, say, earthenware), and hold heat well. Yet, as noted, they rust comparatively hands.[7]

Stainless steel [edit]

Stainless steel finds many applications in the manufacture of kitchen utensils. Stainless steel is considerably less likely to rust in contact with water or nutrient products, and so reduces the try required to maintain utensils in make clean useful condition. Cutting tools made with stainless steel maintain a usable edge while not presenting the adventure of rust found with iron or other types of steel.

Earthenware and enamelware [edit]

Earthenware utensils endure from brittleness when subjected to rapid large changes in temperature, equally commonly occur in cooking, and the glazing of earthenware often contains lead, which is poisonous. Thompson noted that equally a consequence of this the use of such glazed earthenware was prohibited by law in some countries from utilise in cooking, or fifty-fifty from use for storing acidic foods.[eight] Van Rensselaer proposed in 1919 that one test for lead content in earthenware was to let a beaten egg stand in the utensil for a few minutes and sentry to see whether information technology became discoloured, which is a sign that lead might exist nowadays.[9]

In addition to their problems with thermal stupor, enamelware utensils require conscientious handling, as careful as for glassware, because they are prone to chipping. Just enamel utensils are not afflicted past acidic foods, are durable, and are hands cleaned. Still, they cannot be used with strong alkalis.[nine]

Earthenware, porcelain, and pottery utensils can be used for both cooking and serving food, and and then thereby salve on washing-up of two separate sets of utensils. They are durable, and (van Rensselaer notes) "excellent for deadening, even cooking in even heat, such as slow baking". Nevertheless, they are comparatively unsuitable for cooking using a direct heat, such equally a cooking over a flame.[10]

Aluminium [edit]

James Frank Breazeale in 1918 opined that aluminium "is without doubt the best material for kitchen utensils", noting that it is "as far superior to enamelled ware as enamelled ware is to the old-time atomic number 26 or can". He qualified his recommendation for replacing worn-out tin or enamelled utensils with aluminium ones past noting that "old-fashioned black iron frying pans and muffin rings, polished on the inside or worn shine past long usage, are, however, superior to aluminium ones".[eleven]

Aluminium's advantages over other materials for kitchen utensils is its good thermal conductivity (which is approximately an order of magnitude greater than that of steel), the fact that it is largely non-reactive with foodstuffs at depression and high temperatures, its low toxicity, and the fact that its corrosion products are white and and then (unlike the dark corrosion products of, say, iron) do not discolour food that they happen to exist mixed into during cooking.[iv] However, its disadvantages are that it is easily discoloured, can be dissolved by acidic foods (to a comparatively modest extent), and reacts to alkaline soaps if they are used for cleaning a utensil.[12]

In the European Union, the construction of kitchen utensils made of aluminium is determined by two European standards: EN 601 (Aluminium and aluminium alloys — Castings — Chemical limerick of castings for use in contact with foodstuffs) and EN 602 (Aluminium and aluminium alloys — Wrought products — Chemical composition of semi-finished products used for the fabrication of articles for use in contact with foodstuffs).

Clay [edit]

A great characteristic of non-enameled ceramics is that clay does not react with food, does non comprise toxic substances, and is safe for food use because it does not give off toxic substances when heated. Clay is as well an organic compound produced naturally.

There are several types of ceramic utensils. Terracotta utensils, which are made of ruby-red clay and black ceramics. The dirt utensils for preparing nutrient can also be used in electrical ovens, microwaves and stoves, we tin can besides place them in fireplaces. It is not advised to put the clay utensil in the 220-250 temperature oven directly, because it will break. It also is non recommended to identify the clay pot over an open fire.

Dirt utensils do not like sharp change in temperature. The dishes prepared in dirt pots come to be particularly juicy and soft – this is due to the dirt'due south porous surface. Due to this porous nature of the surface the clay utensils inhale aroma and grease. The coffee made in dirt java boilers is very aromatic, just such pots need special intendance. Information technology is not advised to scrub the pots with metal scrubs, it is amend to pour soda water in the pot and allow information technology stay at that place and later to wash the pot with warm h2o. The clay utensils must be kept in a dry out place, so that they will not get damp.

Plastics [edit]

Plastics tin can be readily formed past molding into a diversity of shapes useful for kitchen utensils. Transparent plastic measuring cups allow ingredient levels to be easily visible, and are lighter and less fragile than glass measuring cups. Plastic handles added to utensils amend comfort and grip. While many plastics deform or decompose if heated, a few silicone products can be used in boiling water or in an oven for food preparation. Not-stick plastic coatings tin be applied to frying pans; newer coatings avoid the issues with decomposition of plastics under strong heating.

Glass [edit]

Oestrus-resistant glass utensils can be used for blistering or other cooking. Glass does not conduct rut too as metal, and has the drawback of breaking easily if dropped. Transparent drinking glass measuring cups allow ready measurement of liquid and dry ingredients.

Multifariousness and utility [edit]

Diverse kitchen utensils. At elevation: a spice rack with jars of mint, caraway, thyme, and sage. Lower: hanging from hooks; a minor pan, a meat fork, an icing spatula, a whole spoon, a slotted spoon, and a perforated spatula.

Earlier the 19th century [edit]

"Of the culinary utensils of the ancients", wrote Mrs Beeton, "our knowledge is very express; but as the art of living, in every civilized land, is pretty much the aforementioned, the instruments for cooking must, in a keen caste, bear a striking resemblance to i some other".[13]

Archaeologists and historians have studied the kitchen utensils used in centuries by. For case: In the Middle Eastern villages and towns of the centre beginning millennium Advertizing, historical and archaeological sources record that Jewish households generally had stone measuring cups, a meyḥam (a wide-necked vessel for heating water), a kederah (an unlidded pot-bellied cooking pot), a ilpas (a lidded stewpot/goulash pot type of vessel used for stewing and steaming), yorah and kumkum (pots for heating water), two types of teganon (frying pan) for deep and shallow frying, an iskutla (a glass serving platter), a tamḥui (ceramic serving bowl), a keara (a bowl for bread), a kiton (a canteen of cold water used to dilute wine), and a lagin (a wine decanter).[14]

Ownership and types of kitchen utensils varied from household to household. Records survive of inventories of kitchen utensils from London in the 14th century, in detail the records of possessions given in the coroner'due south rolls. Very few such people endemic whatsoever kitchen utensils at all. In fact only seven convicted felons are recorded as having any. I such, a murderer from 1339, is recorded as possessing simply the one kitchen utensil: a brass pot (one of the commonest such kitchen utensils listed in the records) valued at three shillings.[15] Similarly, in Minnesota in the 2d half of the 19th century, John North is recorded as having himself made "a real nice rolling pin, and a pudding stick" for his wife; 1 soldier is recorded as having a Civil War bayonet refashioned, past a blacksmith, into a staff of life pocketknife; whereas an immigrant Swedish family is recorded as having brought with them "solid silvery knives, forks, and spoons [...] Quantities of copper and contumely utensils burnished until they were like mirrors hung in rows".[16]

19th century growth [edit]

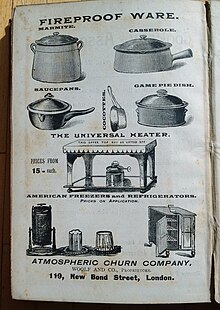

The up-to-engagement kitchen fireproof ware in 1894

The 19th century, particularly in the United States, saw an explosion in the number of kitchen utensils bachelor on the market, with many labour-saving devices beingness invented and patented throughout the century. Maria Parloa's Cook Book and Marketing Guide listed a minimum of 139 kitchen utensils without which a contemporary kitchen would not exist considered properly furnished. Parloa wrote that "the homemaker volition find [that] there is continually something new to exist bought".[17]

A growth in the range of kitchen utensils available tin can be traced through the growth in the range of utensils recommended to the aspiring householder in cookbooks equally the century progressed. Earlier in the century, in 1828, Frances Byerley Parkes (Parkes 1828) had recommended a smaller array of utensils. Past 1858, Elizabeth H. Putnam, in Mrs Putnam's Receipt Book and Immature Housekeeper's Assistant, wrote with the assumption that her readers would have the "usual quantity of utensils", to which she added a listing of necessary items:[18]

Copper saucepans, well lined, with covers, from iii to half dozen different sizes; a flat-bottomed soup-pot; an upright gridiron; sheet-iron breadpans instead of tin; a griddle; a can kitchen; Hector's double boiler; a tin java-pot for boiling coffee, or a filter — either beingness equally good; a tin canister to continue roasted and footing coffee in; a canister for tea; a covered tin can box for bread; one likewise for cake, or a drawer in your store-cupboard, lined with zinc or can; a breadstuff-pocketknife; a board to cutting staff of life upon; a covered jar for pieces of breadstuff, and i for fine crumbs; a knife-tray; a spoon-tray; — the yellow ware is much the stringest, or tin pans of dissimilar sizes are economical; — a stout tin pan for mixing bread; a big earthen bowl for beating cake; a stone jug for yeast; a stone jar for soup stock; a meat-saw; a cleaver; iron and wooden spoons; a wire sieve for sifting flour and meal; a small pilus sieve; a bread-lath; a meat-board; a lignum vitae mortar, and rolling-pin, &c.

— Putnam 1858, p. 318[19]

Mrs Beeton, in her Volume of Household Management, wrote:

The following list, supplied past Messrs Richard & John Slack, 336, Strand, will show the manufactures required for the kitchen of a family in the middle class of life, although it does not incorporate all the things that may be deemed necessary for some families, and may contain more than than are required for others. As Messrs Slack themselves, still, publish a useful illustrated catalogue, which may exist had at their establishment costless, and which it volition be found advantageous to consult by those about to replenish, it supersedes the necessity of our enlarging that which nosotros give:

1 Tea-kettle 6s. 6d. 1 Colander 1s. 6d. 1 Flour-box 1s. 0d. 1 Toasting-fork 1s. 0d. 3 Block-tin saucepans three Flat-irons 3s. 6d. 1 Bread-grater 1s. 0d. 5s. 9d. 2 Frying-pans 4s. 0d. one Pair of Brass 5 Iron Saucepans 12s. 0d. 1 Gridiron 2s. 0d. Candlesticks 3s. 6d. 1 Ditto and Steamer 1 Mustard-pot 1s. 0d. one Teapot and Tray 6s. 6d. 6s. 6d. i Common salt-cellar 8d. 1 Canteen-jack 9s. 9d. 1 Large Boiling-pot one Pepper box 6d. 6 Spoons 1s. 6d. 10s. 0d. 1 Pair of Bellows 2s. 0d. ii Candlesticks 2s. 6d. 4 Atomic number 26 Stewpans 8s. 9d. 3 Jelly-moulds 8s. 0d. one Candle-box 1s. 4d. 1 Dripping-pan and 1 Plate-basket 5s. 6d. 6 Knives & Forks 5s. 3d. Stand 6s. 6d. 1 Cheese-toaster 1s. 10d. 2 Sets of Skewers 1s. 0s. 1 Dustpan 1s. 0d. i Coal-shovel 2s. 6d. one Meat-chopper 1s. 9d. 1 Fish and Egg-slice one Wood Meat-screen 1 Cinder-sifter 1s. 3d. 1s. 9d. 30s. 0d. 1 Coffee-pot 2s. 3d. ii Fish-kettles 10s. 0d.

The Set up £8 11s. 1d. — Isabella Mary Beeton, The Book of Household Management [20]

Parloa, in her 1880 cookbook, took two pages to listing all of the essential kitchen utensils for a well-furnished kitchen, a list running to 93 distinct sorts of particular.[19] The 1882 edition ran to 20 pages illustrating and describing the diverse utensils for a well-furnished kitchen. Sarah Tyson Rorer'southward 1886 Philadelphia Cook Volume (Rorer 1886) listed more than than 200 kitchen utensils that a well-furnished kitchen should have.[21]

"Labour-saving" utensils generating more than labour [edit]

Still, many of these utensils were expensive and not affordable by the majority of householders.[17] Some people considered them unnecessary, too. James Frank Breazeale decried the explosion in patented "labour-saving" devices for the modern kitchen—promoted in exhibitions and advertised in "Household Guides" at the start of the 20th century—, proverb that "the all-time mode for the housewife to peel a potato, for example, is in the quondam-fashioned fashion, with a knife, and not with a patented white potato peeler". Breazeale advocated simplicity over dishwashing machines "that would have done credit to a moderate sized hotel", and noted that the nigh useful kitchen utensils were "the elementary piffling inexpensive conveniences that work themselves into every day utilise", giving examples, of utensils that were simple and cheap only indispensable one time obtained and used, of a stiff brush for cleaning saucepans, a sink strainer to prevent drains from bottleneck, and an ordinary wooden spoon.[22]

The "labour-saving" devices didn't necessarily save labour, either. While the advent of mass-produced standardized measuring instruments permitted even householders with little to no cooking skills to follow recipes and cease up with the desired issue and the advent of many utensils enabled "modern" cooking, on a stove or range rather than at floor level with a hearth, they too operated to enhance expectations of what families would eat. So while food was easier to prepare and to cook, ordinary householders at the same time were expected to prepare and to cook more complex and harder-to-gear up meals on a regular basis. The labour-saving effect of the tools was cancelled out by the increased labour required for what came to be expected equally the culinary norm in the average household.[23]

See besides [edit]

- Kitchenware, list of such wares

- Cookware and bakeware

- Gastronorm, a European size standard for kitchenware

- List of eating utensils

- List of nutrient grooming utensils

- List of Japanese cooking utensils

References [edit]

- Citations

- ^ "Kitchen utensils". GBS.

- ^ Thompson 1969, p. 232–239.

- ^ Parloa 1908, p. xxvi.

- ^ a b Vargel 2004, p. 579.

- ^ van Rensselaer, Rose & Canon 1919, p. 233–234.

- ^ Waggoner, Susan. (2014). Classic household hints : over 500 old and new tips for a happier home. Stewart, Tabori & Chang. ISBN978-1-61312-253-two. OCLC 1028679638.

- ^ a b van Rensselaer, Rose & Canon 1919, p. 235–236.

- ^ Thompson 1969, p. 236–239.

- ^ a b van Rensselaer, Rose & Canon 1919, p. 234–235.

- ^ van Rensselaer, Rose & Canon 1919, p. 236.

- ^ Breazeale 1918, p. 36–37.

- ^ van Rensselaer, Rose & Canon 1919, p. 232–233.

- ^ Beeton 1861, p. 28.

- ^ Schwartz 2006, p. 439–441.

- ^ Carlin & Rosenthal 1998, pp. 42–32.

- ^ Kreidberg 1975, pp. 164.

- ^ a b Volo & Volo 2007, p. 245.

- ^ Williams 2006, p. 67–69.

- ^ a b Williams 2006, p. 68.

- ^ Beeton 1861, p. 31.

- ^ Quinzio 2009, p. 133.

- ^ Breazeale 1918, p. 36.

- ^ Williams 2006, p. 53.

- Bibliography

- Beeton, Isabella Mary (1861). The Volume of Household Management . Wordsworth Reference Series (republished past Wordsworth Editions, 2006 ed.). London: Samuel Orchart Beeton. ISBN978-1-84022-268-5.

- Breazeale, James Frank (1918). Economic system in the Kitchen. Cooking in America (republished by Applewood Books, 2007 ed.). New York: Frye Publishing Co. ISBN978-1-4290-1024-five.

- Carlin, Martha; Rosenthal, Joel Thomas (1998). Food and eating in medieval Europe. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN978-1-85285-148-4.

- Kreidberg, Marjorie (1975). Food on the borderland: Minnesota cooking from 1850 to 1900, with selected recipes . Minnesota Historical Society Press. ISBN978-0-87351-097-iv.

- Parloa, Maria (1908). Miss Parloa'southward New Cook Book and Marketing Guide. Cooking in America (republished past Applewood Books, 2008 ed.). Boston: Dana Estes & Co. ISBN978-1-4290-1274-4.

- Thompson, Benjamin (1969). "On the construction of Kitchen Fireplaces and Kitchen Utensils". In Chocolate-brown, Sanborn Conner (ed.). Nerveless Works of Count Rumford: Devices and techniques . Vol. 3. Harvard University Press. ISBN978-0-674-13953-4.

- Quinzio, Jeri (2009). "Women's Piece of work". Of saccharide and snow: a history of ice foam making . California studies in food and culture. Vol. 25. University of California Printing. ISBN978-0-520-24861-8.

- Schwartz, Joshua J. (2006). "The Material Realities of Jewish Life in the Land of State of israel c. 235–638". In Davies, William David; Katz, Steven T.; Finkelstein, Louis (eds.). The Cambridge History of Judaism: The late Roman-Rabbinic period. Vol. 4. Cambridge University Press. ISBN978-0-521-77248-8.

- van Rensselaer, Martha; Rose, Flora; Canon, Helen (1919). "Kitchen Utensils". A Transmission of Home-Making. Cooking in America (republished past Applewood Books, 2008 ed.). New York: The Macmillan Co. ISBN978-1-4290-1241-6.

- Vargel, Christian (2004). Corrosion of aluminium. Elsevier. ISBN978-0-08-044495-6.

- Volo, James M.; Volo, Dorothy Denneen (2007). Family life in nineteenth-century America. Family unit life through history. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN978-0-313-33792-5.

- Williams, Susan (2006). Food in the United States, 1820s–1890. Food in American history. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN978-0-313-33245-six.

Farther reading [edit]

- Brooks, Phillips V. (2004). Kitchen Utensils: names, origins, and definitions through the ages. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN978-ane-4039-6619-3.

- Matranga, Victoria K. (1996). America at Dwelling house: A Commemoration of Twentieth-Century Housewares, International Housewares Association, ISBN 978-0-9655487-0-0

- Schuler, Stanley; Schuler, Elizabeth Meriwether (1975). "kitchen utensils". The householders' encyclopedia. Galahad Books. ISBN978-0-88365-301-2.

- Byrne, David; Wheeler, Mike (1995). Kitchen Utensils. Science in the kitchen. Longman. ISBN978-0-582-12457-eight.

- Studley, Vance (1981). The Woodworker's Volume of Wooden Kitchen Utensils . Van Nostrand Reinhold Co. ISBN978-0-442-24726-3.

- Shrock, Joel (2004). The Gilded Age. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN978-0-313-32204-4.

- Klippensteen, Kate (2006). Cool Tools: Cooking Utensils from the Japanese Kitchen . Kodansha International. ISBN978-4-7700-3016-0.

- McGee, Harold (2004). "Cooking Methods and Utensil Materials". On Food and Cooking: The Science and lore of the Kitchen. Simon and Schuster. pp. 787–791. ISBN978-0-684-80001-1.

- Hancock, Ralph (2006). "metallic utensils". In Davidson, Alan; Jaine, Tom (eds.). The Oxford companion to food. Oxford Companions Series (2nd ed.). Oxford Academy Printing. ISBN978-0-19-280681-9.

- Lifshey, Earl (1973). The Housewares Story: a history of the American housewares industry . Chicago: National Housewares Manufacturers Association. pp. 125–195.

- Parkes, Frances Byerley (1828). Domestic Duties ; or, Instructions to Young Married Ladies on the Direction of their Household, and the Regulations of their acquit in the various Relations and Duties of Married Life. New York: JJ Harper.

- Putnam, Elizabeth H. (1858). Mrs Putnam's Receipt Volume and Immature Housekeeper's Assistant. New York: Sheldon & Co.

- Rorer, Sarah Tyson (1886). Philadelphia Melt Volume: A Manual of Domicile Economies. Philadelphia: Arnold and Company.

- Wilcox, Estelle Forest (1877). Buckeye Cookery & Practical Housekeeping: Tried and Approved, Compiled from Original Recipes (reprinted by Applewood Books, 2002 ed.). Minneapolis: Buckeye Publishing Company. pp. 364–365. ISBN978-one-55709-515-ii.

- Ettlinger, Steve (2001). The Kitchenware Book. Barnes & Noble Books. ISBN978-0-7607-2332-6.

- Campbell, Susan (1980). The Melt'south Companion. London: Macmillan. ISBN0-333-28790-viii.

External links [edit]

-

Media related to Kitchen utensils at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Kitchen utensils at Wikimedia Commons

chevalierdebefors01.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kitchen_utensil

0 Response to "What kitchen tool used to "cut-in" when baking?"

Post a Comment